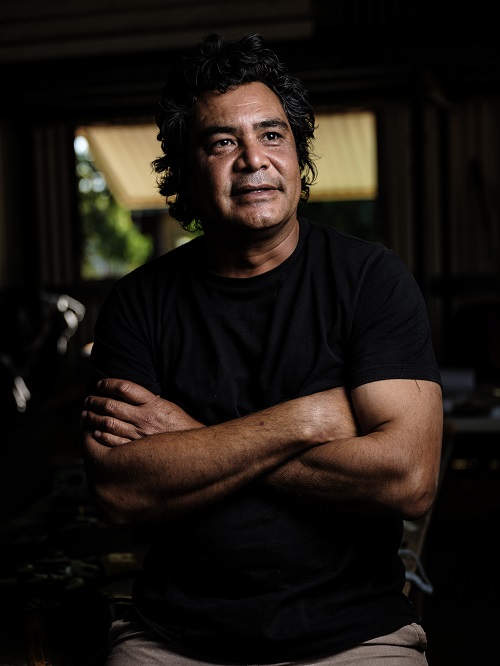

Garry Sibosado. Photography by Michael Jalaru Torres

About the Artist

Garry Sibosado is an artist, designer, and jeweller of the Bard People of the west Kimberley.

Sibosado lives and works at Lombadina, a small community 200 kilometres north of Broome.

Garry’s works are contemporary explorations of traditional Bard creation narratives, kinship systems and culture, made from guwan or pearl shell, the same material used by his ancestors in fashioning of cultural objects.

His works have been exhibited widely, including the Art Gallery of South Australia, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Cairns Regional Gallery, Wollongong Gallery and Western Australian Museum.

Works for sale

Garry’s Undertow work is available to purchase. Visit our sales page for details.

CURATOR’S REFLECTIONS: GARRY SIBOSADO

Garry Sibosado is an artist, designer, and jeweller of the Bard people of the west Kimberley. Garry’s works are contemporary explorations of traditional Bard creation narratives, kinship systems and culture, made from guwan or pearl shell, the same material used by his ancestors in fashioning of cultural objects.

While Garry doesn’t consider himself a politically motivated artist, the way that Garry works and the pace he takes in creating a work is in many ways a comment on the fast pace of contemporary life and the systems of capitalism that manifest as continued and ongoing development in Western Australia and significant environmental and social impact this has on place and people.

Sibosado lives and works at Lombadina, a small community 200 kilometres north of Broome in the north west. Garry’s life, as with the lives of all Bard saltwater people, has been shaped by seas and oceans that surround the peninsula that Lombadina sits upon. These bodies of water sustain Bard people, physically, culturally, and spiritually – they are home to the totemic creatures that provide food for community but also, like the land, waters are imbued with lore – holding the keys to understanding one’s place in the world.

For Garry, as for all seafaring First Nations people, to understand and navigate the water you must also understand and hold knowledge of the sky – they are inherently entwined and interconnected – tides are, after all, made by the pull of the moon, and stories of our human beginnings are etched into the night sky, witnessed by us and our ancestors alike, across the eons.

‘My art reflects my heritage as a saltwater man from the Bard Country in the Dampier Peninsula of the West Kimberley. Although the sea is a constant inspiration for my designs, for this work I have turned my gaze to the skies – to the ‘ocean in the sky’. The stars that make up the Milky Way is what we call ‘Oongoonorr’.

Many cultural creators came from the ‘Oongoonorr’. Symbols within this work include traditional and contemporary icon designs that represent totems of my people, as well as a glimpse of the multitude of stories that our people transfer from generation to generation about the stars.’

Garry Sibosado, Oongoonorr, 2021, mother of pearl, native ebony, cubic zirconia, powder coated steal. Supported by the Western Australian Government through the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries, Artforms and my family. Installation image from John Curtin Gallery. Photography by Robert Frith

CALL & RESPONSE: THE SALWATER SLOW DOWN: GARRY SIBOSADO’S ‘OONGOONORR’ (MILKY WAY), BY EMILIA GALATIS, 2022

The following text was commissioned for Undertow and written following an interview between Garry Sibosado and Emilia Galatis, on January 3rd 2022. Emilia Galatis is an independent curator, author, and arts facilitator with over 15 years of experience working alongside Aboriginal artists and remote art centres in the development and promotion of ambitious creative projects.

“Action on behalf of life transforms. Because the relationship between self and the world is reciprocal, it is not a question of first getting enlightened or saved and then acting. As we work to heal the earth, the earth heals us.” ― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants

The cyclical nature of time mimics the rhythms of nature; as we reach the limits of capitalism perhaps, we can glimpse the tidal motions of our next aeon, but only if we listen carefully. Amongst the relentless development in the State of Western Australia, reciprocity with our natural world seems unfathomable. If Western thought teaches us anything, it’s that everything is a construct, systems created by man that stratify humans as the undisputed leaders. As the last creations to join the other living beings on the planet, I am not sure when we assumed this unquestionable authority. Country is so loud right now, how will we hear the answers? We are floating in the ocean, the sea of possibility; every full moon signals a larger, more powerful tide, we rise and fall in its wake, surrendering to the possibility of reconstruction and rejuvenation.

Over 270 shimmering pieces of pearl shell and crystal comprise Garry Sibosado’s Oongoonorr, his most elegant comment on the contemporary world to date. His personal reflection on the Milky Way, or the ‘ocean in the sky’, synthesises past, present and future, a comment to us all, and a warning of what is lost when we believe that humans can be separated from the whole. Like a shimmering mirage, Oongoonorr poses the world in its entirety, a spiral motif, with everything cycling in its own motion. Garry’s personal reflection on the interconnectivity of all living things creates a space for reflecting on the insidious speed of corporate development in the state of WA.

What is lost when the spirit of the land is caught up in the speed of development? Oongoonorr gently us asks us to assess our own place in the world.

“Everyone thinks that the world is about humans, it’s not. Did anyone ask the whales if we could shoot them with harpoons? Did anyone ask the lizards if we could clear the land?”

Garry Sibosado is a saltwater Bard man who lives in Lombadina. Lombadina is a small community on the Dampier Peninsula about two hours out of Broome. This is important for many reasons; saltwater people have an affinity with the ocean as master and provider; Garry grew up with his elders and showed a natural talent for pearl shell carving. Once a dirt road, the road up to the Cape is now sealed, seeing more visitors than ever. Reading the ocean and fostering a deep affinity with the sea is Garry’s birth right. For Garry there is no distinction between land and water, there is land under the sea after all. In this way, stories of the sky and the sea are both a science and mythology. Water is a highly politicised space in the Kimberley right now, it is hard to talk about the mythology of water without talking about who wants it.

The ocean is at the forefront of identity for Bard people;

“I was looking at the Milky Way and thinking about the ocean, stories that are in the Milky Way. My people are saltwater people, so this is my perception of the Milky Way”.

Garry describes the Milky Way as the ocean in the sky; using pearl shell that comes from the ocean to create a cyclical comment about this connection. He starts by explaining memories he has as a child, laying under the stars, looking up. These early, and formative moments in time are a metaphor for simpler times. For saltwater people, the ocean is not as mysterious abyss – saltwater people navigate the ocean as expertly as the land, using the sky at night as a compass. Capitalism has destroyed our relationship with the natural environment, however for many First Nations people, artworks like this are a cry for change.

Which brings me to slowing down, the art of slowing down. The work is concerned with the speed at which we all move. When we buy food in packetswe don’t foster an active reciprocity with the natural environment. Each piece of pearl shell in this work is painstakingly cared for and buffed; the natural lustre of each pearl shell exquisitely exposed so that there is no aesthetic hierarchy between the man made and natural elements. The insertion of the ebony brings this point home, that story and science are linked; slowing down allows one to use all senses to perceive the world around them.

“People just need to slow down a bit, listen to the world around you, the ocean, the sky, the land, everything. We are not the only creatures here, it’s not our land to destroy. Before us the land, sea and sky are all connected – we use the sky to navigate the water for hunting, even the moon, the tides are way bigger than normal. We use the moon to hunt at night. Take time to smell the leaves, the ocean, to relax, find the peace, find the balance.”

Most of the time my art is my personal connection with my surroundings and environment – in order to teach others, you must have a strong connection yourself.”

Slowing down implies a holistic approach to life where we see the connections between all living things – do we want balance or destruction? The thirst for greater commerce is at the heart of the Western Australian frontier, since colonisation, the Kimberley has been a site of exploitation and foreign invasion, all in search of economic prosperity.

“I am not an overtly political artist but there is a huge push for new development across the whole of the Kimberley. The spirit of the land is lost through these developments, even the tourism is pushing us to do more and meet the demands of external commerce.”

So, I will leave you with something to ponder, out into the ocean and back again, looking up, with reflections upon the realm of the dead;

“The Milky Way is also the realm of the dead, where all the spirits are. The southern cross for example is the eagle/ hawk, an ancestral being. The bull roarer landed near it when it was thrown into the sky by another being down on earth. We use these stories and names to navigate the sky at night when we are on the ocean. You will say the name of those stars from the story, as a navigational tool. Like we will say, stay on this side of the southern cross, don’t pass that side.”